One spring morning, sitting at the table sipping tea, I saw green buds on tree branches hanging over the yard just outside the picture window. The small fists of summer, clenched tight, must have been there for a while, but I hadn’t noticed. Seemingly overnight, the greening buds had swelled and stretched up and out, ready to burst open.

“Tomorrow,” I thought, “maybe the branches will be covered with tiny, new leaves. Or do the green cases hold flowers?” After more than seventy springs, I’m embarrassed to admit, I didn’t know, not having watched trees closely enough. Either way, nature, frozen in place by winter’s cold and long darkness, was moving again in the warmth of spring sun. What other explanation is there for the sudden appearance of green buds?

Perhaps this one: There is no “sudden” in nature. As the Latin phrase goes, natura naturans —”nature naturing,” or to put it another way, nature doing what nature does. Buds don’t pop into existence overnight. They begin forming in the summer or early autumn when temperatures are still warm. Focused on trees’ lush green crowns or their glorious fall colors, we just don’t notice buds, but they are there. By the time we see them in winter, the buds are cloaked with heavy scales or fuzzy cases drawn tightly around them, like your warm woolen coat, pulled close to keep out the cold. And they wait.

So, what was my maple doing all winter? “When cold weather hits, sap descends into roots, and when warm weather arrives, sap rises and feeds the tree,” I thought. Right?

True for most trees, but not for maples. These trees actually suck up the sap when temperatures drop, drawing liquid from the roots, and storing it in branches. A slow freeze with cold nights and warmer days sends sap up and down, up and down, storing more in the sapwood and preparing for a bountiful sap run. When winter hits in earnest, sap waits, frozen, before descending in spring and flowing out of holes if the tree has been tapped. (How this happens and why trees react differently to freeze and thaw is too complicated to explain here. Besides, I wouldn’t do a good job of it. But it’s fascinating and worth an internet search if you’re interested.)

In addition to affecting sap flow, cold winter temperatures send trees into a dormancy period allowing them to survive the harsh season and “wake up” in spring with the energy needed to blossom, resist pests, and develop fruit. When temperatures fluctuate too much from cold to warm during winter, tree buds may open prematurely; the tree may not be able to re-enter dormancy and might not have energy needed for growth.

Dormancy is important. For trees. For us.

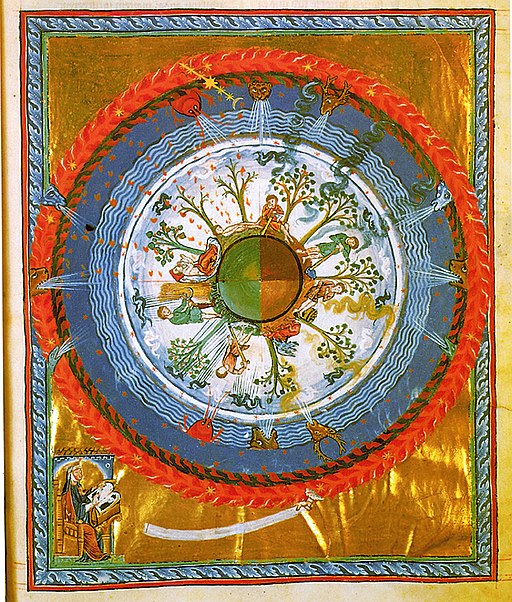

The Word is living, being, spirit, all verdant greening, all creativity. This Word manifests itself in every creature.

Hildegard von Bingen

Sometimes our spirits need to rest. We can’t always be pushing forward, reading more books, attending more workshops, thinking, thinking, thinking. Greedily pulling in information like sap, to feed our hungry souls. Sometimes, what we need is rest. Holding what we already have in quiet. Openness – with no expectations.

Growth is a long process, so slow it often goes unnoticed, in trees and in our souls. Maple buds start forming sometime in the summer but need winter stillness before opening the following year. When warmth tells them it’s safe, they do what they are made to do: They break open. Leaves unfurl to feed the tree and flowers bloom and mature, producing fruit and seeds.

For us, the slow process is growing into who God made us to be. Saint Hildegard of Bingen (1098 – 1179) often used the word viriditas in her writings. It has been translated variously including “vitality,” “growth,” or “freshness.” She used it when writing about plants, healing, and also theologically as a metaphor for the Divine life of Christ that flows through all creation, including us, bringing healing and fruition. Viriditas knows no season; it’s a constant Presence within us. Whether in the quiet of winter or the exuberance of spring, God’s life is at work in our deepest center.

Hasn’t my soul known the same miracle as the buds? Suddenly feeling full of grace after a long winter? Hasn’t yours?

Further reading on St. Hildegard of Bingen, Doctor of the Church

Public Domain Wikimedia Commons

The Life and Works of Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) Fordham University

St. Hildegard gives us a recipe for joy—even during a pandemic by Sonja Livingston in America

Hildegard of Bingen: no ordinary saint by Robdet McClory in the National Catholic Reporter