Painting by Richard Duarte Brown

Originally published in The Catholic Times Oct. 8, 2017

Perhaps it’s because I’m weary of the divisive speech that is becoming more commonplace in our country and of the racism and ignorance of the “other” that undergird it. Maybe it’s hearing hateful comments, seeing intolerance, and recognizing that choices are being made to stoke fear and anger rather that to encourage true listening and dialogue. It’s these things and more that make me read and reread Paul’s words this Sunday, healing, like balm on an open sore:

Finally, brothers and sisters, whatever is true, whatever is honorable, whatever is just, whatever is pure, whatever is lovely, whatever is gracious, if there is any excellence and if there is anything worthy of praise, think about these things. (Philippians 4, 8)

A friend at work gave me a flyer about a unity celebration being held at a local Episcopal church that Sunday evening. I’m glad I went. It was something gracious and lovely that reminded me of the many good people who, in ways large and small, are being love in the world.

A woman opened the celebration with a drum call to gather everyone, including the ancestors. I thought of my parents. Of people who have gone before, working for civil rights. I thought of the communion of saints.

The rector welcomed us and read “Blessing When the World is Ending” by Jan Richardson. It finishes on a hopeful note:

This blessing/will not fix you,/will not mend you,/ will not give you/false comfort;/it will not talk to you/about one door opening/when another one closes./ It will simply/sit beside you/among the shards/and gently turn your face/toward the direction/from which the light/will come,/gathering itself/about you/as the world begins/again.

A young Syrian refugee, 13 when she arrived speaking no English, 17 now, shared her powerful poetry. A woman pastor reminded us that while we look different on the outside, we are the same on the inside and pointed out the fact that human beings are made with two ears and one tongue, perhaps indicating we should listen more and talk less.

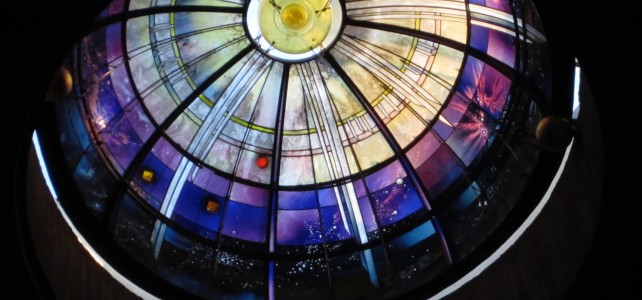

PHOTO: Mary van Balen

Two young women in flowing white dresses gracefully danced their prayer to the One we can’t live without, expressing with their movements the prayer in my heart. An Imam spoke of Islam and respect for all prophets. We listened and learned.

A folksinger led us in “We shall not be moved,” a song loosely based on verses from Jerimiah about one who is like a tree firmly planted by the water surviving drought and yielding fruit. A young girl called out that we should sing for peace. And we did.

A Jewish rabbi considered that we have many names the for same Holy One. She spoke of the prophets of old and wondered about today’s prophets. About being prophets and being bold.

A soloist shook the rafters and sang about God breathing on us, and I felt the Spirit-breath.

A community organizer pulled wisdom from each presentation and put them into questions for us to ponder.

Afterwards, we shared food, listened to stories, and wondered why all churches don’t have evenings like this.

Paul’s final words in that verse from Philippians—Keep on doing what you have learned and received and heard and seen in me. Then the God of peace will be with you—prompted me to consider that what we learn from Paul, he learned from Jesus. What have I learned and heard and seen in Jesus that transforms me?

The Good Samaritan by Vincent van Gogh

In the gospels, I have learned that love, not power, is important. That one’s life doesn’t consist of possessions. That everyone is my neighbor, and I must take care of them. I have seen Jesus heal the sick, feed the hungry, hang out with those on the margins, and eat with outcasts. He was welcoming, patient, and merciful. He was a man of prayer. On his last night on earth he prayed “…that they may be one as we are one—I in them and you in me…” I watched Jesus wash his disciples’ feet and instruct them to do the same. He spoke truth to power, faithfully lived that truth, and was murdered for it.

I heard him say that whatever we do to the least among us, we do to him. And when it came right down to it, when someone asked him what was most important, he had two things to say: Love God. Love your neighbor as yourself.

I heard him say that whatever we do to the least among us, we do to him. And when it came right down to it, when someone asked him what was most important, he had two things to say: Love God. Love your neighbor as yourself.

These are the things we need to keep on doing, each of us bringing the God of peace who dwells in us into our times and places. Through all people of peace, God transforms the world.

© 2017 Mary van Balen

![By Gravure d'Antoine Maurin dit "Maurin l'aîné" (1793-1860) à partir d'un dessin de Louis Janmot (1814-1892) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Pencil drawing of Blessed Fredric Ozanam](http://staging.maryvanbalen.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Frédéric_Ozanam_2-220x300.jpg)

Originally published in The Catholic Times Aug. 13, 2017

Originally published in The Catholic Times Aug. 13, 2017

Originally published in The Catholic Times, November 12, 2016 issue

Originally published in The Catholic Times, November 12, 2016 issue