Last week I made an impromptu visit to a state park. My sister and her husband are avid birdwatchers, and while I’m not, they suggested we could enjoy dinners and evenings together after having filled the day with what feeds our souls.

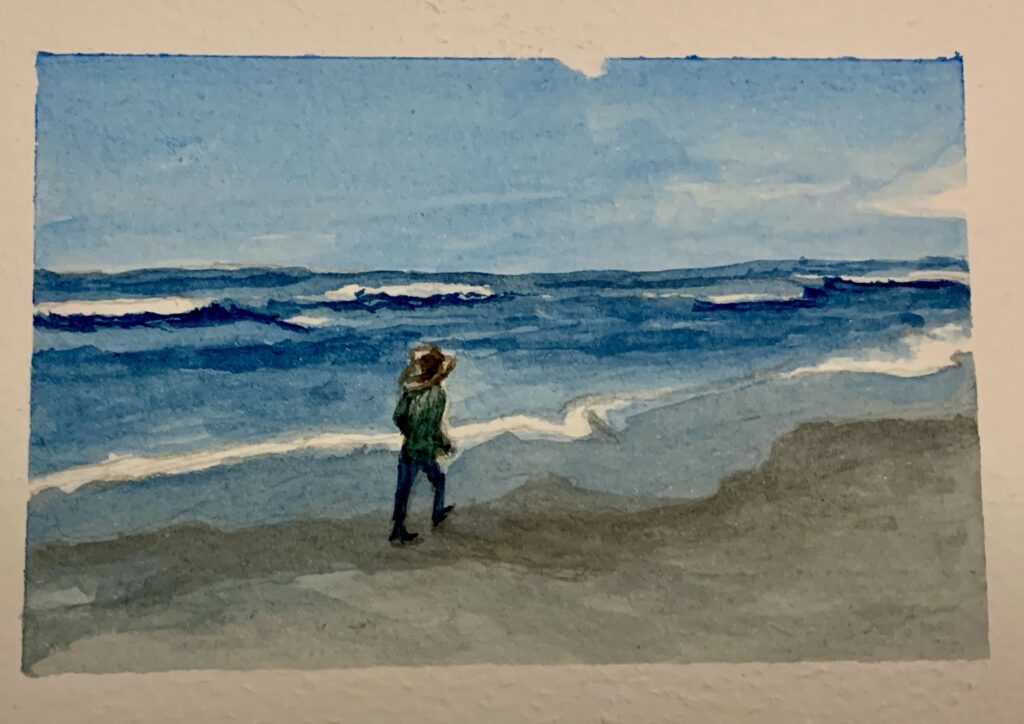

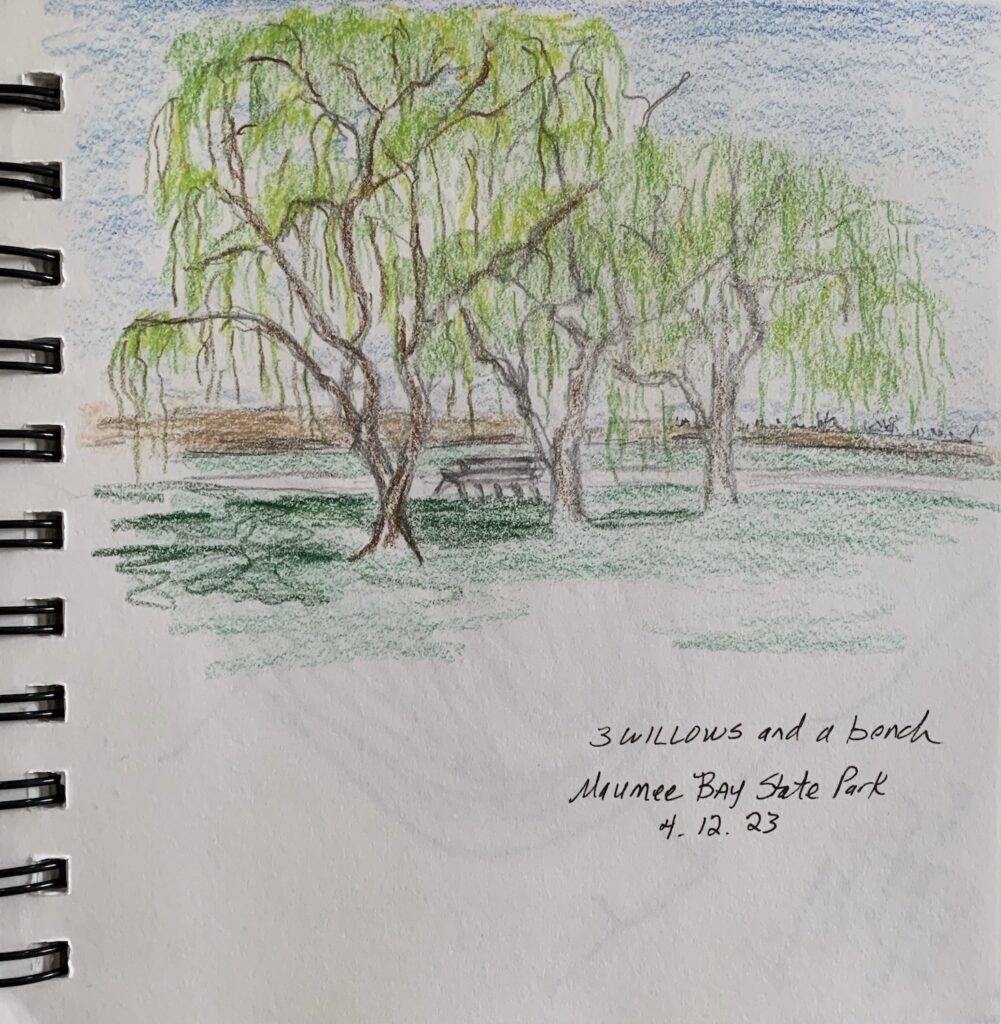

The simple change of scenery lifted my spirits. While the lodge that sat on the edge of Maumee Bay and Lake Erie had no long beach to walk, there was a large body of water. Constant wind off the lake lifted and swayed the graceful branches of weeping willows just beginning to bloom. And though the boardwalk and marshy land around it had changed drastically since my last visit decades ago, it provided a place very different than my suburban neighborhood to walk and observe nature.

I wasn’t sure exactly how I’d fill my time, so I brought Mary Oliver’s collection of poetry, Thirst, colored pencils and watercolors, a sketch pad and journals, and pastries from my favorite bakery. Even though I live alone, the solitude and quiet offered by this space felt different, more intentional.

In the mornings I sat outside on the small patio sipping coffee and eating a palmier. I read the first half of Mary Oliver’s poems aloud, imagining the wind carrying the words to the dancing willow trees, the Canada Goose on the pond, and skimming them across the water. The words, like Tibetan prayer flags, releasing grace as the wind blew them along.

An arthritic knee kept my walks on the short side, but I took lots of them. White tail deer and I startled one another along the marshy patch where they were wading and nibbling tender sprouts. A muskrat, finding the spring greens irresistible too, pushed aside watery plants, leaving dark trails behind. A black snake slithered from rock into water, smoothly curving its body this way and that and disappeared into leafy growth on the opposite side. Turtles sunned themselves on a log. Ducks hung around in little cove, and birds flitted from branch to branch.

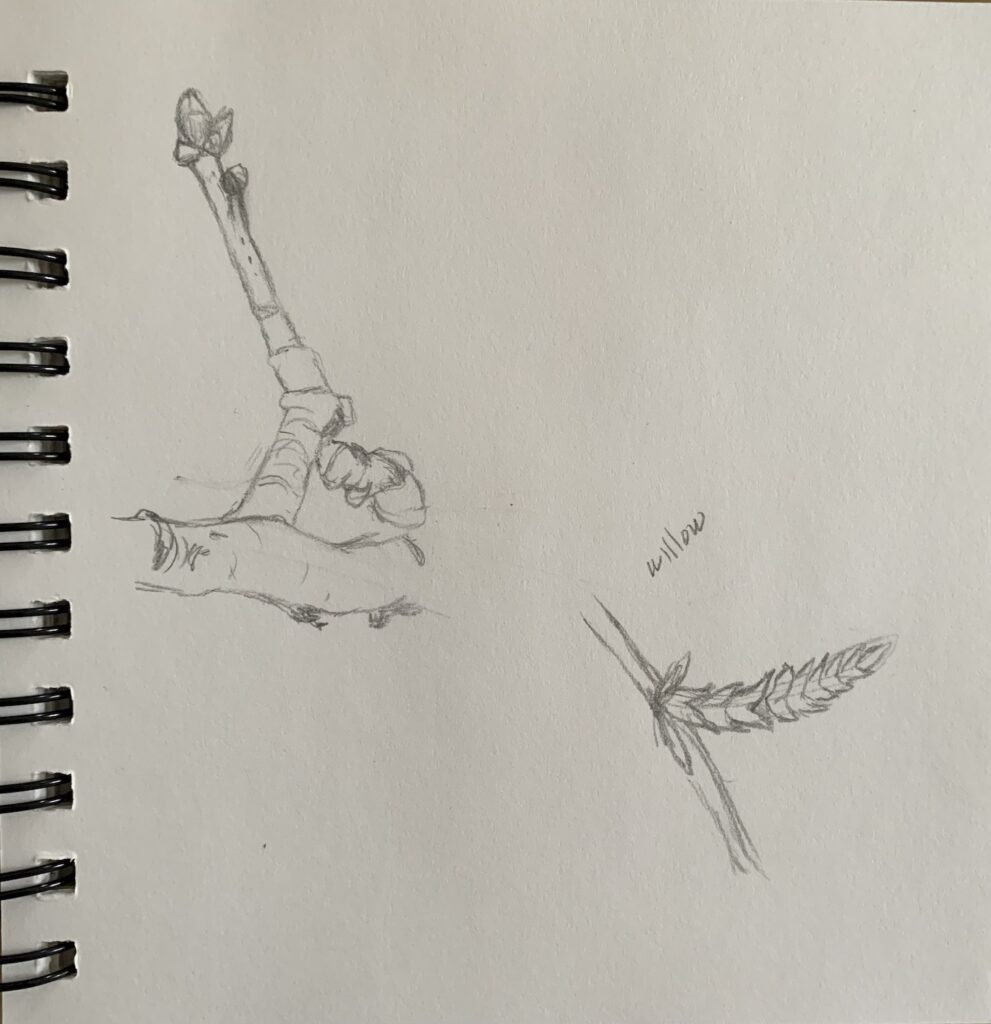

I ended up with some sketches—the bench beneath the willows, my mug of coffee and a palmier resting on a napkin, a small feast I required myself to draw before eating it, and buds of the willow and a tree I’d need leaves to identify—none great art, but I did pay more attention to how the palmier dough was looped into its butterfly shape and how leaves and buds appear in the spring. The process was a mindfulness exercise reminding me of a favorite book, The Zen of Seeing: Seeing/Drawing as Meditation by Frederic Franck.

I read all of Thirst, pondering some lines: “My work is loving the world / … which is mostly standing still and learning to be astonished….” (from “Messenger”); “And they call again, ‘It’s simple’ they say, / ‘and you too have come / into the world to do this, to go easy, to be filled / with light and to shine.’” (from “When I Am Among the Trees”)

I ate a delicious walleye dinner and some creamy Easter chocolate from home. My sister, her husband, and I watched the new episode of Ted Lasso and shared walks and conversation in the evenings.

All in all, a lovely time. I didn’t accomplish anything particular. But that was the point. What I needed. To be still with myself and with God, wasting time together with no goal in mind other than being who I am.

Too often these days, I am overwhelmed with sadness and anger and a sense of not being enough. I think many of us struggle with this. It’s easy when we live in a world where so much is broken. Where suffering and injustice surround us, and we feel powerless to change it. Where communication and connection are fraught by deep ideological divisions, both political and religious. And then there is Covid, still hanging around.

When I returned home, I listened to this season’s last podcast of On Being’s with Krista Tippett and U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy, titled “To Be A Healer.” His words resonated, as if he had known just why I needed that short time away.

Dr. Murthy said he believed our greatest source of strength comes from our ability to give and receive love. He talked about the importance of having a sense of self-worth, of trusting who we are and what we hold inside. Our mental health, he suggests, is the fuel we need to function at our best. We need a “full tank” to be present to ourselves, to one another, to our communities, and to the world.

Sometimes I’m running on fumes.

He suggested four things to help people improve their overall sense of wellbeing and social connection that combat the stress of loneliness and disconnect with ourselves and others. Listen to the podcast to hear them all. The last surprised me: Solitude. It shouldn’t have. Isn’t that what intentional quiet time, quiet prayer, or meditation is? His explanation: “The solitude is important because it’s in moments of solitude, when we allow the noise around us to settle, that we can truly reflect, that we can find moments in our life to be grateful for.”

For me, it’s also a time to be still and open to the Grace always given. A time, as Mary Oliver’s trees suggested, to be filled with light and to shine.

What are your times? Where are your places?

Sources

Messenger by Mary Oliver

The Zen of Seeing: Seeing/Drawing as Meditation by Frederic Franck

Vivek Murthy: To Be A Healer Interview On Being with Krista Tippett

Photos: Mary van Balen